Tai-Shan Schierenberg, a Briton with a Chinese mother and German father, first distinguished himself in 1989 when he won the National Portrait Gallery’s John Player Portrait Award. Since then several of his portraits have been hung in the National Portrait Gallery and his commissions have included a double portrait of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. He also appears as one of the judges in the Sky Arts series Portrait/Landscape Artist of the Year.

His latest exhibition, New Work, comprises a dozen paintings, both portraits and landscapes, in addition to three oil paint-encrusted three-dimensional heads of polystyrene created with colours scraped daily from his painting palette. His paintings are inspired both by features of everyday life as well as found images.

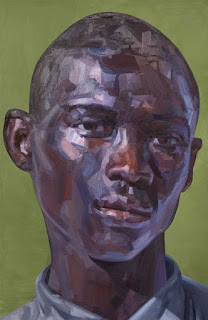

In the window of the gallery hangs Balthasar (above), an interpretation of an image he found in a newspaper. To view it within the gallery necessitates getting very close up. In doing so, one can see clearly the artist’s technique of broad converging brushstrokes in a patchwork verging on abstraction. With distance, outside the gallery window, one sees a rather beautiful portrait of a man with a gentle expression with an array of bright colours emphasising the light falling upon his dark skin.

That palette range is Schierenberg’s signature, acquired during his formative years as a painter in the Black Forest in Germany which he has continued to visit ever since he was a small child. His father is from a family in Frankfurt who was moved to the Black Forest towards the end of the war when food was scarce in the cities.

“After he met my mother in London, he dragged us all out there and we’d go and mow the hay with scythes, chop wood and kill goats - it was very much a medieval existence,” he tells me.

The sense of alienation and fearfulness he has always felt about the place, is captured in Quarry Road Winter - Black Forest (left) with its intimidating rocks, oppressively encroaching on the roadway as the warmth of the sky begins to fade. Once again that bright palette range gives the rocks definition and a certain character with a hint of optimism perhaps beneath the Gothic facade.

Schierenberg describes his father, a fellow painter, as a “monster” yet he keeps returning to this area of southern Germany with which his father is identified. “I miss the landscape. It’s a part of the texture of my being but when I’m there, there is a tension. I don’t know if I’m very happy there but it makes a fruitful ground for painting. “

A much softer landscape is that of East Anglia where Two Bushes, Norfolk (below) was painted. It’s impressionistic in which broad brushstrokes convey a sense of harmony within the flux of nature. Such landscapes provide the artist with fertile ground for experimentation.

“Instead of making a tree by painting the colours you see and putting them into the form it appears in a conscious way, it’s more about putting on approximations and scraping and seeing stuff working through the bottom and having paint running out the back of your brush, approaching the subject from an oblique point of view. I like the idea as an artist of always trying to surprise yourself or breaking your boundaries in a way.”

“Instead of making a tree by painting the colours you see and putting them into the form it appears in a conscious way, it’s more about putting on approximations and scraping and seeing stuff working through the bottom and having paint running out the back of your brush, approaching the subject from an oblique point of view. I like the idea as an artist of always trying to surprise yourself or breaking your boundaries in a way.”

An emerging theme in Tai-Tsan Schierenberg’s work are depictions of groups of men. His last exhibition included a group of footballers. One painting in the exhibition, Leap of Faith shows a group of 21 male swimmers preparing to dive into icy waters to retrieve a crucifix thrown into the water by a priest. It’s a common ritual practised by followers of the Orthodox Church in Bulgaria and Russia. It holds associations with male spirituality and identity and, he admits, has a lot to do with the relationship with his father.

Though Schierenberg normally works with single figures, it was the lurid green hue of his nephew’s anorak that inspired him to paint Brother and Child (left). As he painted the pair, he acknowledged the psychological subtexts that developed. It looked like his brother was holding his younger self, for example, which Schierenberg emphasises by almost melding the two bodies together by the brother’s ear. There’s a sentimentality here certainly, tenderness in the inclination of the child’s head and the way his hands are placed, and contrast in their expressions, the child’s having a hint of confrontation. The portrait is simple in form but with more complex connotations which can be said of many of New Work's paintings in general.

New Work is showing at the Flowers Gallery, 21 Cork Street, London W1S 3LZ until 25 March.

All images are used with the permission of the artist and gallery.